As I think everyone knows who's even heard of the play, Tennessee Williams based Laura on his sister Rose. Here they are in New York.

This, of course, was after Rose's lobotomy at the age of 28. Can we talk about lobotomies for a second? Lobotomies are hideous. The fact that they were ever even a marginal portion of medical science is despicable, let alone that they were in use for twenty-some years (between the 30s and 50s) as a cure for mental diseases - like Rose's schizophrenia.

Here are some cringe-worthy facts about lobotomies:

Here are some cringe-worthy facts about lobotomies:- The point of a lobotomy is to cut some of the connections inside your brain.

- The methods for doing this were varied and fascinating, ranging from drilling holes in a patient's skull and destroying brain tissue with alcohol, to putting an ice pick into a patient's eye socket and pounding with a hammer.

- The first doctor ever to perform a lobotomy, a Swiss psychiatrist named Gottlieb Burckhardt, said (I'm paraphrasing, but this is the gist), "There are two kinds of doctors - the "do no harm" kind and the "something's better than nothing" kind. I'm of the second kind." He later shut down his research because - shocker! - it was making people nervous.

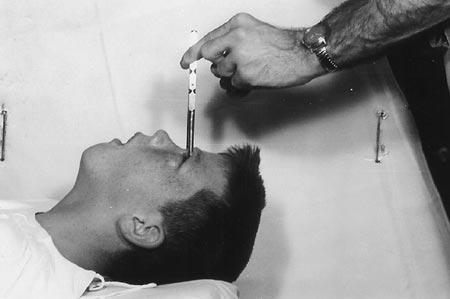

- Lobotomies were the golden children of state mental hospitals, which didn't always have the facilities for anesthesia. So the major proponent of lobotomies in America, a real sicko named Walter Freeman (that's him there working on a patient), suggested that they use electroshock therapy instead.

Are you vomiting yet?

I'm going to say it again: Rose was 28.

And thanks to this brilliant breakthrough in medical science, Rose had to be institutionalized for the rest of her life.

Let's think for a second. Without Rose's lobotomy, we wouldn't have Laura Wingfield or Blanche DuBois. We wouldn't have the bitter indictment of the treatment of the insane in "Suddenly, Last Summer." We would have lost a good deal of the energy that drives Tennessee Williams' marvelous plays. And Rose might have lived her adult life like an adult. And the people to whom this was done (did I mention that the patient's consent wasn't a big deal?) might not have shut down and lost the basic control over their lives and actions that we take for granted.

Was it worth it?